Film Music for Piano Trio, Volume 2

*** THIS PERFORMANCE IS SOLD OUT ***

Here is the the second program of an upcoming series of film music for piano concerts by Eriko Makimura.

“FILM MUSIC FOR PIANO TRIO, VOLUME 2”

Hélianne Blais (violin)

Samira Dayyani (cello)

Eriko Makimura (piano)

Date: Saturday, April 24, 2010. Doors: 19:00. Concert: 20:00. Electric café: 22:00.

Venue: Den Collinske Gaard, Copenhagen.

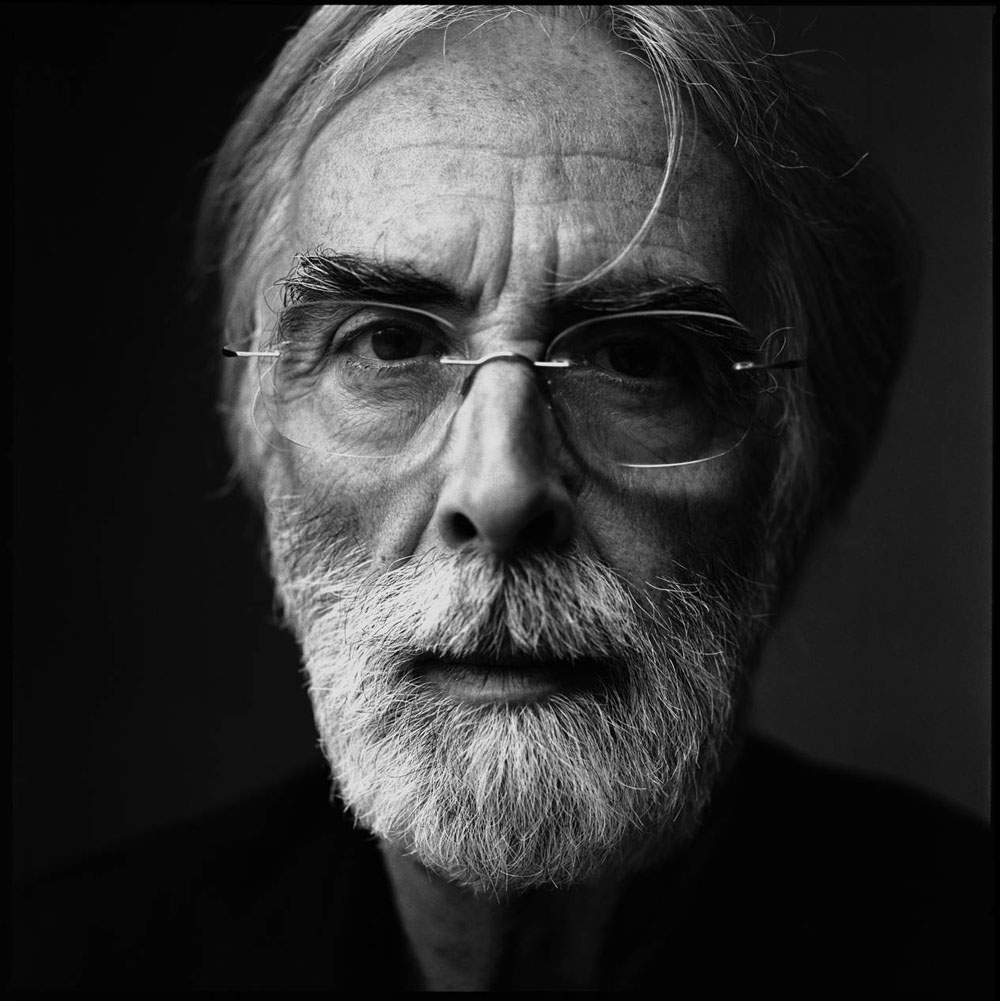

(Photo: Michael Haneke)

1. J.S. Bach “Prelude and Fogue in C Minor BMV 847” (1722)*

2. Franz Schubert “2nd Movement “Andante Con Moto” from Piano Trio No. 2 in E Flat Major D.929 (Opus 100)” (1828)**

3. Sergei Rachmaninoff “Variations on a Theme of Corelli for piano” Opus 42 (1931)**

4. Maurice Ravel “Piano Trio In A Minor” (1914)***

*From Michael Haneke’s “La Pianiste” (2001)

*From Stanley Kubrick’s “Barry Lydon” (1975)

**Original Corelli composition from the Merchant Ivory production of “Jefferson In Paris” (1995)

***From Claude Sautet’s “Un coeur en hiver” (1992)

Read about “Film Music for Solo Piano, Vol.1” here.

*** THIS PERFORMANCE IS SOLD OUT ***

6 Comments

Other Links to this Post

-

Tweets that mention Eriko Makimura » Film Music for Piano Trio, Volume 2 -- Topsy.com — March 28, 2010 @ 14:44

-

Ravel’s Klavertrio i A-mol (1914) | chambermusic.dk — April 18, 2010 @ 19:38

-

Franz Schubert’s Klavertrio i Stanley Kubrick’s “Barry Lyndon” | chambermusic.dk — April 18, 2010 @ 20:00

RSS feed for comments on this post.

By Ronnie Rocket, April 18, 2010 @ 14:02

The Variations on a Theme of Corelli, Opus 42, were written in 1931 and make use of a well known theme that the seventeenth century violinist-composer Arcangelo Corelli had used as the basis of a set of variations in the twelfth of his solo violin sonatas. The melody, La folia, known in French as Les folies d’Espagne, was among the most popular tunes of the Baroque period, appearing variously as a dance, song or theme for instrumental variations, whether in The Beggar’s Opera, in the work of Vivaldi, Handel or Bach. The melody makes an appearance in the work of Cherubini in Paris in the early nineteenth century and was used in 1863 by Liszt for his Rapsodie espagnole and by Carl Nielsen in 1906 in his opera Maskarade.

Rachmaninov, in his series of twenty variations on La folia, a forerunner of his later Paganini Variations, wrote the only solo piano work of his exile, a sign of a measure of restored confidence, after the relative failure of his Fourth Piano Concerto in 1926. The Paganini Rhapsody followed in 1934 and the Third Symphony in the years immediately following. The Corelli Variations are a masterly exploration of the possibilities of this simplest of original material. The work is conceived as a unity, with an Intermezzo, in fact a cadenza, before the fourteenth variation, and final rapid variations leading to a gentle coda. The Variations represent a new phase in Rachmaninov’s interrupted career as a composer, where a tendency to greater clarity of texture is coupled with considerable harmonic originality and daring.

http://www.classicsonline.com/catalogue/product.aspx?pid=1951

By Ronnie Rocket, April 18, 2010 @ 14:12

There is wide latitude as to how Rachmaninoff’s works are interpreted. The problem here deals with interpretation based on an intuitive level rather than a systematic approach in identifying stylistic idiom from the basis of the composer’s unique writing style. Consequently, this study examines Rachmaninoff’s Corelli Variations and its performance problems while addressing fundamental research question at hand: in matters of ontology and epistemology, is there a singular interpretation that is privileged over another? Expressly, how do criteria for legitimacy come into play when music interpretation is informed, not just by written notation but also by an aural tradition supported by an aesthetic sensibility? And if so, what are the guiding principles that make an interpretation authentic? By incorporating interpretivism, a philosophical framework that values multiple reality, subjectivity, and stability, this investigation employs a new research paradigm in music while providing sound solutions. This research should be useful to pianists, fans of Rachmaninoff’s work and anyone who may be interested in the tradition of music interpretation.

http://www.amazon.com/Interpreting-Rachmaninoffs-Variations-Theme-Corelli/dp/3639177266

By Ronnie Rocket, April 18, 2010 @ 14:25

This was the last original solo piano work by Rachmaninov and the only one he composed outside Russia. It was written in 1931, the same year the composer boldly denounced the Soviet Union, referring to its leaders as “Communist grave-diggers.” Stalin banned Rachmaninov’s music as a result, but, recognizing its more appealing and generally less radical nature, rehabilitated it three years later. This work is among the several that were subsequently well received in Moscow.

The Variations on a Theme of Corelli was written in Rachmaninov’s less Romantic, more detached style, already heard in his Piano Concerto No. 4 (1926; rev. 1941) and the much earlier Piano Sonata No. 2 (1913). But the Corelli Variations go a step further in their icy, emotional demeanor, for here Rachmaninov displays a cerebral temperament more so than in any other composition in his oeuvre.

The work is cast in three movements, Allegro and Scherzo, Adagio, and Finale. The outer panels are in D minor, and the inner one in D major. The “Corelli” theme is elegant and pristine, sounding quite unlike Rachmaninov’s normal style. Thirteen variations follow to fill out the first movement. The first is lively and easily related to the opening theme, the next three are a little slower, with growing complexities. Variations five through seven are faster and inclined toward divulging rhythmic aspects of the theme, though the music remains generally delicate and lean, almost Classical-sounding.

Variations 8 through 13 form the last group in the first movement. The first here is marked Adagio misterioso and establishes a sort of musical haze from which even the livelier variations in this section do not completely break free. The ninth is among the most beguiling, its thematic thread and haunting harmonies imparting a sense of mystery and desolation. Some of the faster music in the succeeding variations is reminiscent of the writing in the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini.

There is a brief Intermezzo following variation 13 and a reprise of the original theme, but now in D major. The two second movement variations, 14 and 15, are slow and sound closest to Rachmaninov’s more Romantic style.

The Finale consists of variations 16 through 20 and the coda. The first of these is colorful and lively, the second delicate and somewhat exotic, some of the harmonies tinged with a slightly eastern flavor. The last three variations are the most muscular of all, featuring big, brilliant chords and powerful fortes. In the coda, the mood subsides, its thematic morsels are reminiscent of the slower music in the first movement of the Piano Concerto No. 4.

Curiously, Rachmaninov stipulated in the score that variations 11, 12, and 19 could be omitted, even though their presence is hardly superfluous. After performing this work for several seasons, the composer abandoned it and never played it again. In the end, while this music sounds like Rachmaninov, it is clearly representative of his drier, less Romantic side. A typical performance of the work lasts about 18 to 20 minutes.

http://www.answers.com/topic/variations-on-a-theme-of-corelli-for-piano-op-42